How Babble's eye tracking (calibration) works

Intro

One thing I have been asked time and time again is how our eye tracking works, and how it differs from other headsets. For starters, our production eye tracking model estimates normalized gaze as well as normalized eye openness. To date, inference takes 5 millisecond on the high end with average inference taking about 10 milliseconds, and has an accuracy within ~5 degrees.

Our model is pre-trained on approximately 4 million synthetic frames and 30k real frames. These metrics were taken before we implemented our eye data collection program, which to date has seen 1,200 submissions from 240 unique users.

This is as far as any similarities go. In order for our eye track to work, we train a neural network on your device following an eye tracking calibration.

Calibration

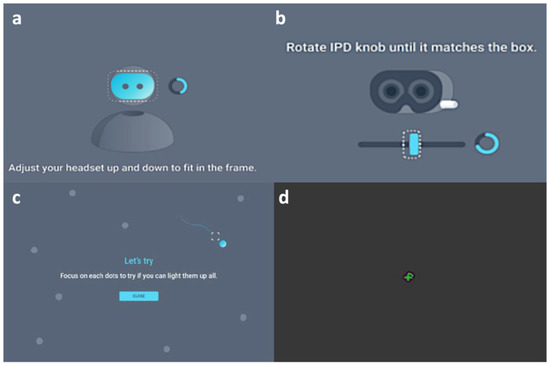

When you calibrate a VR headset's eye tracking, it typically contains a strong general model that requires only a little fine-tuning on top. With the eye tracking calibrations of the Vive Pro Eye, Varjo Aero or Quest Pro, etc., the process is a little like this:

- You adjust the vertical position of the headset.

- You adjust the IPD (interpupillary distance) of the headset. Some headsets can do this automatically, like the Varjo Aero and Samsung Galaxy XR.

- Here is where the fine-tuning takes place. You look at a 5 or so points at the extremes of the headset's FOV, essentially determining where the absolutes (up, down, left, right) of your gaze are.

When you introduce differing VR headsets, you encounter a handful of issues:

- Different headsets have different fields of view. That is to say, a dot's relative position to the edges(s) of a headset may vary.

- Some headsets may have eye relief, some may not.

- Some users may wear glasses, corrective lens inserts, and these too may vary from headset to headset.

While we could train a model to account for this, we would need a lot more data than we have. Instead, our approach is to train a simpler general model that specializes on the user's eyes during calibration.

However, we still have to deal with the above issues. To collect eye information, we prompt the user to do the exact opposite of the above. Instead of remaining still and following a moving eye calibration dot, the calibration dot itself remains still and the user moves their head!

Below is the (stretched) eye tracking calibration tutorial we display to users in their headset. Here, the dot remains stationary and the user rotates their head around:

After this there is a separate tutorial in which the user is prompted to close their eyes for ~20 seconds to calibrate eye openness. Training the neural network takes 5-10 minutes depending on what hardware is available to train on.

Implementation

Our eye tracking calibrator went through 3 major revisions:

Unity

We pioneered things in Unity to prove that such a method could work. We did consider shipping the Unity overlay as is, however, we were hesitant as it wasn't in line with our open source goals, and would introduce another level of bloat to the project.

OpenVR

While the Unity prototype was developed, a separate project was created in parallel. It was lighter, smaller, and it recreated the same features via a barebones OpenVR overlay. This was ultimately the tool we shipped until version v1108.

This was also the version we demoed at Open Sauce 2025. Thank you to everyone who donated eye data at the convention! However, a number of users reported several usability concerns:

- For the eye tracking calibration to work, you must be facing forward in your VR playspace. While we prompted users in text/gave them time to orient themselves, many users struggled to find which way was forward in their playspace.

- There were issues with the tutorial video playback mechanism, sometime the video would lock up or not play at all.

- Antivirus would flag our overlay as malware and prevent the application from working

- The overlay was inherently Windows-exclusive. While there was a successful attempt to port things to Linux with Proton, there was only 1 and was quickly outdated. Additionally we could not port this to other platforms, such as macOS or Android.

Developer concerns

More worrying was our inability to improve the OpenVR Overlay.

Pulling down the trainer repo, you would be greeted by ~20,000 lines of C++ code across four files (one containing 10,000 lines) with little documentation. To build, you would need a specific version of Visual Studio's 2019 build chain as well as a system wide install of OpenCV.

For reference, our current production overlay has 1500 lines of code.

This was the natural evolution of the overlay in question. Over its development of six months, the OpenVR overlay saw every iteration, every failed and successful experiment for an eye tracking algorithm. Every feature that was added to the app was subsequently piled onto the previous experiment.

What we really needed was a flexible tool that could accommodate future experiments and changes, as well as work with the current production trainer.

Godot

When researching other frameworks, I had a handful of criteria:

- Said framework would need to support Windows and Linux builds, with the ability to ship to macOS, Android, etc in the future

- Said framework would still function as an OpenVR overlay, enabling it to be used while other games were running in the background.

- Said framework would have a compatible software license, in support of our open-source roots.

I looked at a number of tools: Unity, Unreal, Flax Engine, Raylib, but I also considered the team's ability to adopt the framework as well: This would effect our ability to collaborate on things going into the future. The one framework that really ticked all these boxes, would be the Godot engine, despite our collective inexperience with it.

This is where I introduce FrozenReflex. He is the most cracked Godot developer I know, so I reached out to him and explained the nature of the project. He agreed to work with us on a project and thus began a six-month contract, which turned out to be an amazing learning experience. More on this later!

The Godot OpenVR Plugin

Out the get-go, we were hit with a problem: The Godot OpenVR Plugin wasn't working for us. Textures would swap around at random, and the app would crash seemingly randomly.

Here, the floor is the tutorial and the tutorial is the floor.

I hear you saying: "Godot 4 has native OpenXR support and we wouldn't need any kind of plugin to handle VR support, right?"

Not quite. OpenVR and OpenXR, despite their overlaps, are far from the same. TL;DR, the only way for an OpenVR application to run above another is to have it act as an OpenVR overlay. OpenXR has overlays, they are not compatible as/with OpenVR overlays.

This feature is essential. Users overwhelmingly prefer to perform eye tracking calibrations in within a Social VR context. We did consider using Godot 3 to build the overlay, however this would introduce its own issues.

Swapped Textures

When the above texture swap would happen we saw this in our logs: Could not create overlay, OpenVR error: 17.0, VROverlayError_KeyInUse. Shoutout to vilhalmer on the GodotVR team, they were able to narrow down the cause:

You can read more about the fix in this Github PR.

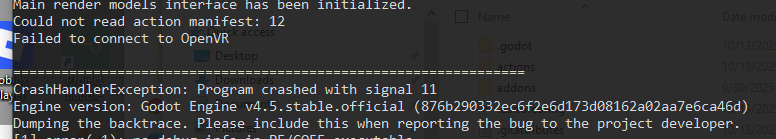

Missing Manifests

These are FrozenReflex's finding's, credit to him on this section.

In addition to the texture swapping, we also getting another mysterious error:

At a high level, an OpenVR manifest is a file that describes to OpenVR what controller input is needed for an application to work. These handle things like controller input, haptics, and more.

However, this file was being produced. Poking around some more, the only place in the entire plugin codebase where set_action_manifest_path (where the above error was coming from) was in this block:

// If we found an action manifest, use it. If not, move on and assume one will be set later.

if (manifest_path.length() != 0) {

String absolute_path;

if (os->has_feature("editor")) {

absolute_path = project_settings->globalize_path(manifest_path); // !

} else {

absolute_path = exec_path.path_join(manifest_path); // !

}

if (!set_action_manifest_path(absolute_path)) { // !

success = false;

}

}

success was being set to false because the set_action_manifest_path method failed:

if (manifest_data.is_empty()) {

Array arr;

err = FileAccess::get_open_error();

arr.push_back(err);

UtilityFunctions::print(String("Could not read action manifest: {0}").format(arr));

return false;

}

What does success get used in?

if (success) {

/* create our head tracker */

head_tracker.instantiate();

head_tracker->set_tracker_type(XRServer::TRACKER_HEAD);

head_tracker->set_tracker_name("head");

head_tracker->set_tracker_desc("HMD tracker");

XRServer *xr_server = XRServer::get_singleton();

if (xr_server != nullptr) {

xr_server->add_tracker(head_tracker);

}

/* reset some stuff */

for (int i = 0; i < vr::k_unMaxTrackedDeviceCount; i++) {

tracked_devices[i].tracker = Ref<XRPositionalTracker>();

}

device_hands_are_available = false;

left_hand_device = vr::k_unTrackedDeviceIndexInvalid;

right_hand_device = vr::k_unTrackedDeviceIndexInvalid;

// find any already attached devices

for (uint32_t i = vr::k_unTrackedDeviceIndex_Hmd; i < vr::k_unMaxTrackedDeviceCount; i++) {

if (is_tracked_device_connected(i)) {

attach_device(i);

}

}

}

Setting up a lot of important stuff, it seems! The problem is that absolute_path is set to a valid path in the editor, and invalid in the export. globalize_path and path_join do extremely different things.

globalize_pathtakes ares://oruser://paths and converts it to a real global pathpath_joinis the same as C#, conjoins paths in such a way that you don't need to worry about separator characters per platform

However, we don't care about user input. We don't deal with any signals or user input at all! We commented this out and that resolved the problem immediately.

(Meme by RedInjector)

Reception

The new overlay was received warmly by our community, that touted its cross-platform nature and stability. In terms of new features the Godot overlay bolsters:

- It has an OpenVR backend, an OpenXR backend for Linux and Android, and a desktop backend for fast debugging.

- Better calibration dot placement/user orientation.

- Enhanced audio, previously we could only play procedural sounds.

- Enhcaned video, moving to Godot fixed video playback entirely.

- Native Linux and Android support, macOS support down the road.

Shoutout again to FrozenReflex and RedInjector for their amazing talents, this would not have been possible without you both.

After the initial release, we added a feature that enables users to re-train individual expressions. Suppose you liked the way your eye gaze came out, but not your blink. Previously you would need to train every expression again, now you can just choose one at a time. To my knowledge, no one else has this feature.

Reflections

Prior to this, I had no Godot experience. I come from a background in Unity development, having worked on interactive exhibits for museums. I can now see myself using the Godot engine in a professional context. I get how scenes work, the similarities and differences between Godot and Unity C#, how gdscript works and so much more.

Additionally, I learned a lot about team management. I'll write about this in another blog post. Thanks for reading, until next time:

- Hiatus